GLOBAL VISION, LOCAL REACH: Achieving Sustainability in Global Health**

Imagine that a young Indian medical student visits the U.S. for a period of two weeks. She volunteers at a local health clinic and talks to a few Americans. Later, she goes back to India and claims to have played an important part in solving the problem of rising U.S. healthcare costs. She goes on to independently write an academic paper for a prestigious journal on the U.S. healthcare system. Would a perspective that she developed over two weeks accurately represent the complexity of the U.S. healthcare system? If her paper is published, it may become the archetype for the U.S. healthcare system, even though it was written by someone who hasn’t experienced the problem first-hand [1]. Although this seems like something that should not happen, it unfortunately is not uncommon in the field of international medical work.

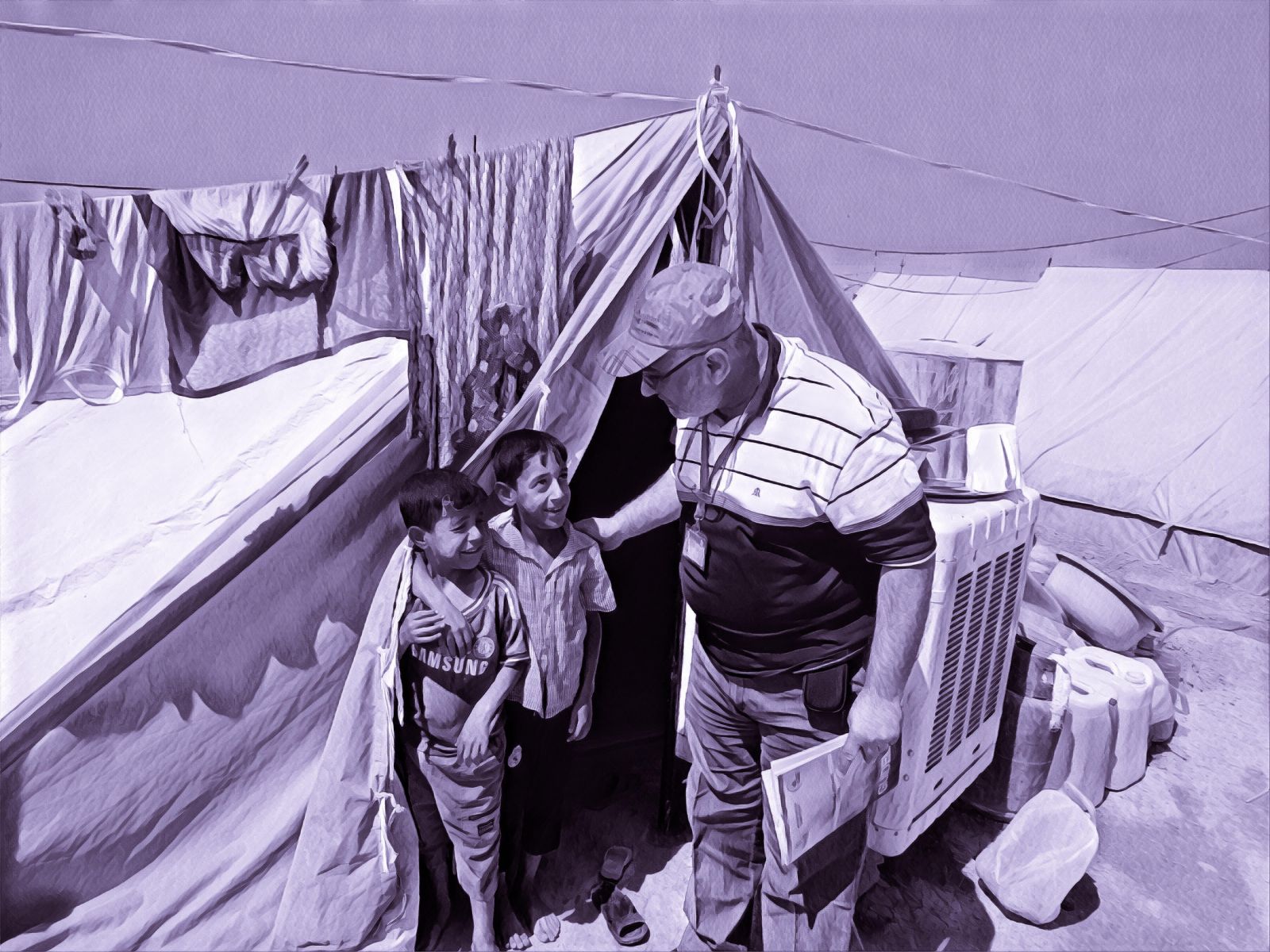

European and American researchers often visit low-to-middle income places like India or Africa, where they seek to conduct research, assist the “needy,” and offer solutions based on their short-lived experiences [2]. This practice is termed “white saviorism,” where a white person attempts to help a non-white person in ways that may ultimately be beneficial to the white person or harmful to the non-white person. White saviorism is grounded in colonialism, through which Western perspectives are held at a higher standard to local opinions, which ultimately get ignored or excluded from the conversation [3]. While these trips may often be well-intentioned, they can produce drastic consequences for the local community in question if not grounded with clear expectations, local partnerships, and long-term program evaluation.

Bach independently handled medical care for these children, which included delivering blood transfusions and inserting IV catheters. Over 100 of them died.

Barbie Savior, a satirical Instagram account with over 100,000 followers, brings this concept to the internet. With a bio reading, “It’s not about me…but it kind of is,” Barbie Savior’s content includes Barbie in different African settings “snapping selfies with the less fortunate” and “passing out blessing bags full of candy and hope” [4]. While the account is a clever rendition of the saviorism concept and attempts to put a funny spin to global volunteerism, it is anything but fictional. Unfortunately, there have been several cases where foreigners—whether they are drawn to this field due to academic purposes or are well-intentioned but misinformed—have destroyed local communities and harmed people’s health, all in the name of “helping the less fortunate”.

A recent example is the infamous Renee Bach, an American who moved to Uganda at the age of 20 to start a nutrition center called Serving His Children for malnourished children in the region. Despite having no medical training or a health license, Bach took in 940 severely malnourished children over a period of five years. Bach independently handled medical care for these children, which included delivering blood transfusions and inserting IV catheters [5]. Over 100 of them died. It is worthwhile to note that the standard of care for this population usually involves advanced medical treatment at a licensed healthcare facility. Bach, however, ignored all the regulations and rules, because she “felt like it was a calling from God”. After an advocacy group filed a lawsuit against Serving His Children on behalf of two mothers whose children died at the center, Bach returned to the U.S., where she continues to deny any wrongdoing on her part [6]. Bach’s example, where an inexperienced foreigner’s intentions resulted in irreversible damage to a community’s health, is still included in global health literature due to the nature of its work.

The high costs, time, effort, and logistical constraints intrinsic to any global health work can cause international medical work to be short-term, usually in the form of electives or internships [7]. This is termed “medical tourism” which is defined as “short-term overseas work in poor countries by clinical professionals from rich countries” [8]. However, as in Bach’s example, not all volunteers who embark on medical tourism are certified clinical professionals with the appropriate expertise to engage in medical work. Medical tourism imposes burdens on local health-care facilities and provides short-term relief without addressing the root causes of health problems [7].

Therefore, these are short-term “band-aid” solutions that often do more harm than good since they are not accompanied with long-term preventative measures and follow-up for program evaluation [9]. In fact, such interventions ultimately only benefit the volunteers by giving them opportunities for self-development, personal growth through travel, university credits, work experience, and a feeling of “giving back” [9]. This leads to systemic harm, as the presence of Western doctors often viewed as “superior” by the local community undermines the knowledge and authority of local professionals [10]. Therefore, these short-term medical trips can be ineffective and inappropriate because they create additional barriers for patients, which “reinforces health disparities and perpetuates the cycle of poverty” [10]. These barriers include undermining of existing local services, lack of long-term access to health services, and inappropriate care provided by the volunteers.

Long-term local partnerships in global health work should be firmly grounded in clear expectations to ensure sustainability of the venture.

With increased public awareness and opportunities for global connectivity, the field of global health is continuously gaining more interest. There are two divergent approaches that are usually taken to implement a global health program — the top-down and the bottom-up approaches. While the top-down approach involves coordinating efforts at a national or centralized level, the bottom-up method develops interventions in the affected communities through local efforts [11]. These approaches are often seen as mutually exclusive, where the top-down focuses on regulation and policies and bottom-up focuses on community action [11]. However, when siloed, these two approaches can have several disadvantages such as lack of integration of community members or limited resources. Therefore, a combination “nut-cracker” approach that combines top-down centralized action with the bottom-up force of the community is essential to the success and sustainability of any global health venture, including medical tourism [12].

This combination approach has been shown to be more effective than either of the siloed approaches in other areas of healthcare [13]. For instance, a teamwork training system that was delivered for implementation to different rural Iowa hospitals by either approach or combination found that combination hospitals were the most successful in implementing the system while the ones that received only one approach struggled to implement the system due to lack of top-level administrative support or lack of team involvement [13].

Meaningfully involving the ‘local’ in global is the only sustainable way to improve health outcomes and truly give back to the community.

This principle of combining national and local efforts can be translated to the sphere of medical tourism, where national efforts by governments or centralized agencies such as the World Health Organization in combination with the localized efforts of community members and non-profits will lead to powerful and sustainable results. This involves forming long-term local partnerships and standardizing regulations to hold short-term foreign volunteers accountable and prevent disasters from occurring in the global health realm.

Long-term local partnerships in global health work should be firmly grounded in clear expectations to ensure sustainability of the venture. Some of the characteristics of a successful partnership include: a favorable political or social environment, mutual respect and trust, mutual sharing of stakes, informal relations between members, shared vision and concrete goals, skilled leadership, and sufficient funds and resources [14]. It is easy to see that with the unequal balance of responsibilities and the dependence on funds common to any local-global partnership, it is challenging to form a “partnership” in its truest sense. Therefore, global health work should incorporate “a community-based participatory” lens, where community members, researchers, and other stakeholders are equitably involved in the research process and the collaborative knowledge is used to achieve a common goal [15]. This approach helps involve community members at every step of the research process and promotes and recognizes community strengths and skills. Eventually, this ensures long-term sustainable changes for the community that last long after the project has been completed [15]. One such example of a successful partnership model is that of Kybele, an international non-profit that focuses on childbirth safety. Their model involves four key principles: recognizing the need for partnership involvement; engaging “champions” from the local community who are well-versed in local culture, requirements, and bureaucracy; obtaining stakeholder support by engagement; and using data to maintain transparency among partners [16]. In the Kybele model, a “champion” is usually a mid-career professional who is selected early in the process and is involved in every aspect of programming. A personalized plan is made for each project that actively involves the input of the community. Face-to-face training and on-site visits are extensively used to build and maintain local relationships [16]. This model has been successfully implemented in several countries such as Serbia, Croatia, and Ghana [16].

There are several inefficiencies that need to be fixed in order to truly achieve long-lasting impact that involves the community at every step of the way, but innovating regulations and building community partnerships is definitely a step in the right direction. Evidence-based literature must be utilized to assimilate successful models like Kybele and the nutcracker approach in elements of medical tourism. Meaningfully involving the “local” in global is the only sustainable way to improve health outcomes and truly give back to the community.

**Editor’s Note: this article appears on the 2020 print issue as “Doctor’s Office or Travel Agency: The Dangers of Medical Tourism”.

Work Cited:

- Pai, M. Global health still mimics colonial ways: here’s how to break the pattern. The Conversation http://theconversation.com/global-health-still-mimics-colonial-ways-heres-how-to-break-the-pattern-121951.

- White savior. Wikipedia (2019).

- Horton, R. Offline: Is global health neocolonialist? The Lancet 382, 1690 (2013).

- Barbie Savior (@barbiesavior) • Instagram photos and videos. https://www.instagram.com/barbiesavior/.

- American With No Medical Training Ran Center For Malnourished Ugandan Kids. 105 Died. NPR.org https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2019/08/09/749005287/american-….

- Arnold, A. American Woman Accused of Letting Hundreds of Ugandan Kids Die at a Fake Clinic. The Cut https://www.thecut.com/2019/07/renee-bach-pretended-to-be-a-doctor-in-ug… (2019).

- Suchdev, P. et al. A Model for Sustainable Short-Term International Medical Trips. Ambulatory Pediatrics 7, 317–320 (2007).

- Bezruchka, S. Medical Tourism as Medical Harm to the Third World: Why? For Whom? Wilderness & Environmental Medicine 11, 77–78 (2000).

- Bauer, I. More harm than good? The questionable ethics of medical volunteering and international student placements. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines 3, (2017).

- The Significant Harm of Worst Practices. http://www.uniteforsight.org/global-health-course/module8.

- Global Health: Evolving Paradigms. Medscape http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/701805.

- Baum, F. E. Cracking the nut of health equity: top down and bottom up pressure for action on the social determinants of health. Promotion & education 14, 90–95 (2007).

- Stewart, G. L., Manges, K. A. & Ward, M. M. Empowering Sustained Patient Safety: The Benefits of Combining Top-down and Bottom-up Approaches. Journal of Nursing Care Quality 30, 240–246 (2015).

- Wildridge, V., Childs, S., Cawthra, L. & Madge, B. How to create successful partnerships—a review of the literature. Health Information & Libraries Journal 21, 3–19 (2004).

- Collins, S. E. et al. Community-based Participatory Research (CBPR): Towards Equitable Involvement of Community in Psychology Research. Am Psychol 73, 884–898 (2018).

- Ramaswamy, R., Kallam, B., Kopic, D., Pujic, B. & Owen, M. D. Global health partnerships: building multi-national collaborations to achieve lasting improvements in maternal and neonatal health. Global Health 12, (2016).